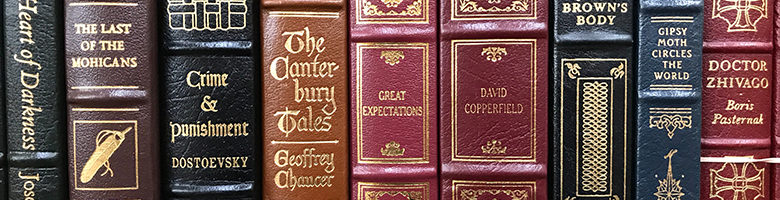

Great Expectations

We recently changed our internet provider. That sentence made many of you shudder, and you groaned a little without even knowing it. If you have been an adult more than a few days and have cable, internet, or any other wired or quasi-wired service coming to your house, apartment, or tiny home, you already know what I’m going to talk about.

In Charles Dickens’ novel, Great Expectations, Pip has great expectations about becoming wealthy, being a gentleman, and getting the girl of his dreams, Estella. Having “expectations” in the nineteenth century specifically meant that you expected to inherit some money after the death of a family member. Dickens probably also had great expectations about the financial success of his serial novel at the time. We all have expectations—dreams, hopes, and plans—about our lives and the way things will go for us. And, like Pip, those expectations often go unmet.

Expectations have both affective (emotional) content and cognitive content. When the emotional content of our expectations gets ahead of the cognitive content, we start expecting what we are wishing for. In other words, when our desires become strong enough, they drown out the rational voice that tells us what we are hoping for is unlikely.

When our inappropriate expectations are unfulfilled, we can experience significant resentment. Notice that I said, “inappropriate.” Inappropriate expectations exceed cognitive reasonability and include content we have no control over. This happens when we are not realistic about the balance between our wishes and our rational assessments about how much we can shape reality.

The ancient philosopher Epictetus advised, “Do not seek to have events happen as you want them to, but instead want them to happen as they do happen, and your life will go well.” This may be a little too stoic for some, but it is pointed in the right direction. Healthy expectations result when I acknowledge that circumstances (and people) are not under my control, but my imagination and emotional attachments are.

When I need to interact with the service people of any of the wireless or wired service providers, I might expect that they will be courteous, efficient, and helpful. Much of the time, that apparently exceeds cognitive reasonability. My emotional and mental assertion that I deserve to be treated better only leads to resentment. The only thing I have control over is whether I choose to do business with them or not.

The same is true for everyone else. When people interact with us, as leaders, as friends, as family, or collectively as a community or a company, they have certain expectations. Sometimes those expectations are unreasonable, but most often they are within a certain band of acceptability. When we fail to meet those expectations, it results in negative emotions and the corresponding behaviors. Like me with the internet company, the only choice they really have is whether to interact with us or do business with us.

My experience with the internet installer went well. He was on time, informed, courteous, and got us up and running quickly and without any problems. I was pleasantly surprised and when asked (he said they will send a survey), I will give him a positive review. He exceeded my expectations (good for him), and I had relatively low expectations (good for me) to begin with.

We each have the ability to control our own expectations to head off resentment. We can also be proactive and determine what other people expect of us so we can try to meet those expectations or help readjust them. Expectations can be great if they are reasonable and understood by both parties.

As an organization, we must realize that our customer’s expectations are constantly changing and do our best to respond. As individuals, we can be clear with the people around us about what they can (and cannot) expect from us. Working to short circuit the expectations/resentment loop positions ourselves (and others) to appreciate what does happen, and it is The Kimray Way.