Limits of Power

I just finished reading Malcolm Gladwell’s “David & Goliath.” I know, it came out several years ago. So, I’m a little behind on my reading pile. Nevertheless, I found the book fascinating.

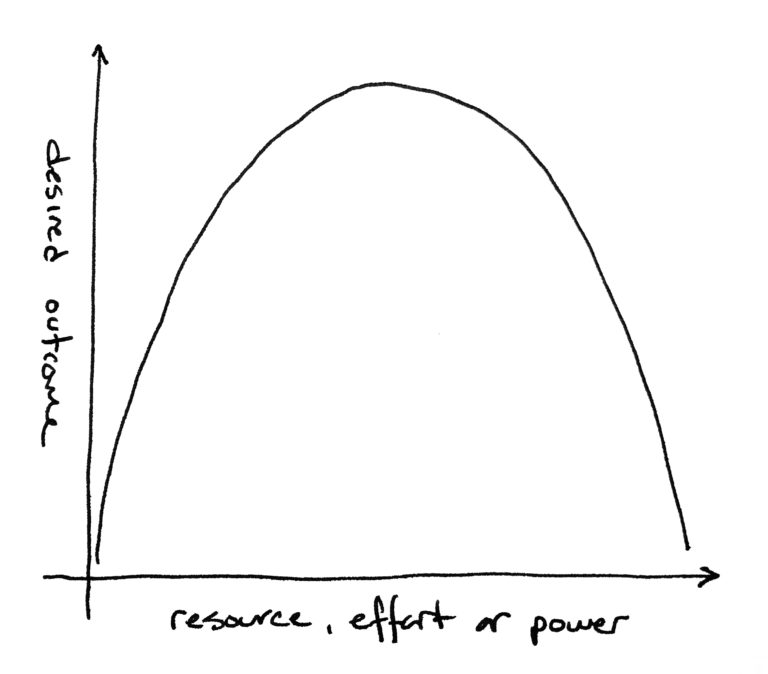

Gladwell knits together several stories about very different people and circumstances to define a thesis: there is an inverted curve function when it comes to the efficacy of resources related to a desired outcome.

This means there is a sweet spot of effort, resource, or power that produces the maximum effect or outcome. Apply less and you don’t get the best result; apply too much and the results start going down too.

As leaders, we have power. Sometimes it is called authority. We can tell people what to do. We can create incentives (positive or negative) to motivate people. We have some control over some things. However, that power has very real limits, and when used improperly or excessively, it produces declining results and progressively worse outcomes.

There are some things that impact where the breakover point on this curve is. In other words, effort put into these other things impacts both the arc of the curve (how optimum the outcome can be) and the balance of resource or effort that is required to achieve it.

Legitimacy of authority is often overlooked and underappreciated. Lessons from history abound where the more powerful and better armed or equipped party failed to conquer the underdog. In “David & Goliath,” Gladwell talks about how far superior U.S. forces wer in Vietnam, and yet we could not prevail over the North Vietnamese. Much has been said or written about our failures in that “war,” but not much about the lack of legitimacy we had to be there. The very people we were there to “save” did not see us as saviors, but as usurpers. I don’t mention this to engage in a debate about that particular era, but rather as an example of how “might does not always make right.” Having power over someone, if that power is not legitimate, can in fact be worse than not having power at all. You expend all the resources and effort to achieve nothing.

Where does legitimacy for power come from? Mostly it comes from “fair” and wise use of that power. I put “fair” in quotes because that word has some issues associated with it, but most people use it to mean that one person doesn’t benefit in excess or at the expense of another. Legitimacy also derives from the motivation behind the use of power. Why we do things is often more important than what we do. Using our power to advance ourselves is the fastest way to lose legitimacy. Using power to advance our “buddies” is probably the second fastest way.

Legitimate power or authority is appropriate power or authority. That sounds simple but is actually very difficult to define further. At Kimray, we do not extend our authority at work to when people are away from work, as that would be inappropriate. Our drug policy, which prohibits the use of controlled substances at all times (and thereby extends to time when people are not at Kimray) is not an extension of our power, it is us agreeing that the law of the land has legitimate power.

A single claim by a member of the community does not necessarily equate to a lack of legitimate authority. For instance, a child screaming at his mom, “you’re not the boss of me,’ does not make her authority illegitimate. However, when the people we lead question our authority, our response should be to question ourselves and validate that we have behaved in ways to create legitimacy.

Our authority must be legitimate, and it must also have the permission of those we wish to lead. This sounds odd at first. “This is my job and I have the responsibility to direct things,” you might say. And you are partially correct. By accepting a job at Kimray we each give our permission to be governed at some level by those in authority. That is the technicality. The reality is much more nuanced. We tend to give ourselves over to leadership we trust and believe in, and resist leadership when we question their motives.

By saying we have permission to lead, we are not saying that we sit a person down and ask, “Will you give me permission to lead you?” Rather we are talking about the posture that people take to our leadership. When we have their permission, we have their participation and collaboration. Leading without permission is like pushing people where you want them to go. Leading with permission is like being on an adventure where everyone wants to go where you are going and works to keep up and with the group.

If we are to be effective leaders at Kimray, or anywhere else, we must have transparent motives, act in accordance with our belief that everyone has equal value, and engage our teams intimately in what we are doing so they are as much a part of it as we are. If we don’t, we will find ourselves continually pushing people and rounding up the stragglers. If we do, we will be leading an eager group wanting to reach the next ridge as much as we do. Not only is it a more effective use of resources (including our power), it is the right thing to do, and it is The Kimray Way.